The Last Days of Imperial Japan

Japan experienced unparalleled destruction by U.S. military forces during World War II, resulting in its complete capitulation. Washington played a decisive role in Tokyo’s postwar transition and reconstruction, but the legacy of Japan’s imperial wartime actions continues to be a source of tension with its Asia-Pacific neighbors.

Yalta Conference

The Allied leaders—U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin—agree to the conditions under which the Soviet Union will enter the war in the Pacific against Japan. Soviet involvement, with the opening of a new front, is seen as crucial to the conclusion of the war. Under the Yalta agreement, Japan’s surrender would lead to the return of territory imperial Russia lost during the 1904–05 Russo-Japanese War, including southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands.

Battle of Iwo Jima

U.S. forces battle Japanese troops for control of the strategic island of Iwo Jima. The U.S. mission, Operation Detachment, is the amphibious invasion [PDF] of the island after months of aerial and naval shelling. The battle is one of the bloodiest in Marine Corps history, killing nearly seven thousand U.S. Marines and more than twenty thousand Japanese soldiers in the thirty-six days of fighting. The island later serves as an emergency landing site for U.S. B-29 bombers.

Great Tokyo Air Raid Begins

The United States launches an extensive air campaign, dropping more than two thousand tons of incendiary explosives on Tokyo over two days. The bombardment leaves Tokyo in ruins, destroying nearly sixteen square miles. An estimated eighty thousand to one hundred thousand civilians die. The Tokyo air raid is the first in a series of firebombings on sixty-four Japanese cities.

Battle of Okinawa

Hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops battle Japanese forces on Okinawa. The island is a potential staging ground for air bases deemed vital for Allied wartime efforts in the Pacific. The battle is even bloodier than Iwo Jima, with more than fourteen thousand U.S. troops killed and seventy thousand Japanese soldiers killed. Up to 150,000 civilians, one-third of Okinawa’s population, die in the cross fire. The U.S. “island hopping” campaigns, ahead of a projected invasion of Japan, prove exceedingly costly and help influence U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s decision to use atomic weapons.

Germany’s Surrender Ends World War II in Europe

Nazi General Alfred Jodl signs the complete and unconditional surrender of all German armed forces at Allied headquarters in Reims, France, ending the war in the European theater. May 8 is declared Victory-in-Europe (V-E) Day. After the defeat of Nazi Germany, Allies’ battle focus turns to the Pacific theater.

Panel Recommends Using Atomic Bomb

The Interim Committee, a secret high-level group tasked with advising President Truman on nuclear issues, recommends using the atomic bomb against Japanese military targets as soon as possible and without prior warning because the potential loss of U.S. life in an invasion of Japan would be unacceptably high. President Roosevelt had launched the Manhattan Project in 1942 with the aim of developing an atomic bomb. As research advances, Truman’s advisors debate plans to invade Japan and to use an atomic bomb.

Truman Threatens Japan With Destruction

President Truman warns Japan that it will face the same complete destruction of Germany if it does not surrender. As the president weighs whether to drop an atomic bomb on Japan or invade, a series of studies by military planners estimate high casualties of U.S. forces in the planned offensive; projections vary from 1.2 million casualties with 267,000 deaths to 4 million casualties with 800,000 deaths.

U.S. Tests Atomic Bomb

The U.S. Army completes the world’s first atomic weapons test at the Los Alamos research site in New Mexico as part of the Manhattan Project. On July 24 at the Potsdam Conference in Germany, Truman informs Stalin of U.S. plans to use an atomic weapon on Japan. The following day, Acting Chief of Staff Thomas T. Handy sends a directive to General Carl Spaatz authorizing the use of the bomb on preselected Japanese cities any time after August 3, once weather permits.

Potsdam Declaration

Leaders of the “Big Three”—the United States, Soviet Union, and Great Britain—gather in Potsdam, Germany, to negotiate the terms to end World War II in Europe. Separately, Churchill, Truman, and Republic of China President Chiang Kai-shek issue the Potsdam Declaration outlining the terms of Japan’s surrender, including the unconditional surrender of armed forces, disarmament, and occupation of Japanese territory by Allied forces. Japanese leaders reject the declaration on July 28.

U.S. Drops Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima

The United States drops the world’s first atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Between sixty thousand and eighty thousand people die instantly, with thousands others injured and thousands more dying from burns and exposure to radiation. The city suffers extensive destruction, with nearly 67 percent of structures obliterated. In a speech announcing the bombing, Truman threatens Japan’s complete destruction: “If they do not now accept our terms they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.”

Soviet Union Declares War on Japan

Foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov announces the formal Soviet declaration of war against Japan. Soviet troops begin their march on Manchuria, Chinese territory invaded by Japanese forces in 1931. At the end of World War II, millions of Japanese nationals are repatriated from China. In the Soviet Union, thousands of Japanese soldiers are forced into hard labor [PDF] as prisoners of war. Most are repatriated in the first four years after the war, but the last major group of Japanese prisoners is sent back in 1956.

U.S. Drops Atomic Bomb on Nagasaki

The Bockscar, a U.S. B-29 bomber, drops a second atomic bomb over the industrial valley of Nagasaki. An estimated forty thousand people are killed in the explosion; thousands of others later die from burns or radiation exposure. The yield of the explosion over Nagasaki is later estimated at around 21 kilotons, 40 percent greater than the Hiroshima atomic bomb.

Japan Agrees to Surrender

In a radio address to the Japanese public, Emperor Hirohito announces Japan’s acceptance of the terms outlined in the Potsdam Conference for its unconditional surrender. Allied powers celebrate the day as Victory Over Japan (V-J) Day, which effectively marks the end of World War II.

Allied Occupation of Japan Begins

General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP), arrives at Atsugi Air Base to begin the Allied powers’ occupation of Japan. Unlike occupation in Germany, the SCAP is granted direct control over Japan’s main and immediate surrounding islands, while outlying territory is divided among Allied powers. Tasked by President Truman to oversee the occupation, MacArthur seeks to democratize Japan’s political system and liberalize its economy, emulating a U.S. model.

Japan Signs Formal Surrender

Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signs the Instrument of Surrender on behalf of Emperor Hirohito on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, thereby ending all hostilities and agreeing to all provisions of the Potsdam agreement for Japan’s complete and unconditional surrender. Shortly after, a convoy of more than forty U.S. ships enters the bay with thirteen thousand troops ahead of Japan’s official occupation. During the occupation, the Allied powers establish tribunals to address war crimes and oversee Japan’s political transition.

Hirohito Calls on MacArthur

Emperor Hirohito calls on General MacArthur at the U.S. embassy in Tokyo, marking the first time that an emperor of Japan travels in person to see another leader. This ten-minute exchange is the first meeting between the two, and Hirohito reportedly expresses responsibility for Japan’s wartime actions. Though effectively stripped of real power, Hirohito remains an important symbolic figure. Historians say the Truman administration and MacArthur believed that maintaining Hirohito as head of state provided a stable political climate to enact reforms in Japan.

Closing of U.S. Japanese Internment Camps

Months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt issues an executive order authorizing the imprisonment of people with Japanese heritage in camps, forcing thousands to close businesses and abandon their homes. The first camps open in February 1942, and more than 110,000 people, most U.S. citizens, are detained in the next four years. U.S. Supreme Court rulings uphold the constitutionality of Roosevelt’s order, but the government begins releasing detainees in early 1945. The last camps officially close in March 1946. After a decade-long campaign by Japanese-American activists, the U.S. government agrees in 1988 to formally apologize and provide $20,000 in reparations to each survivor.

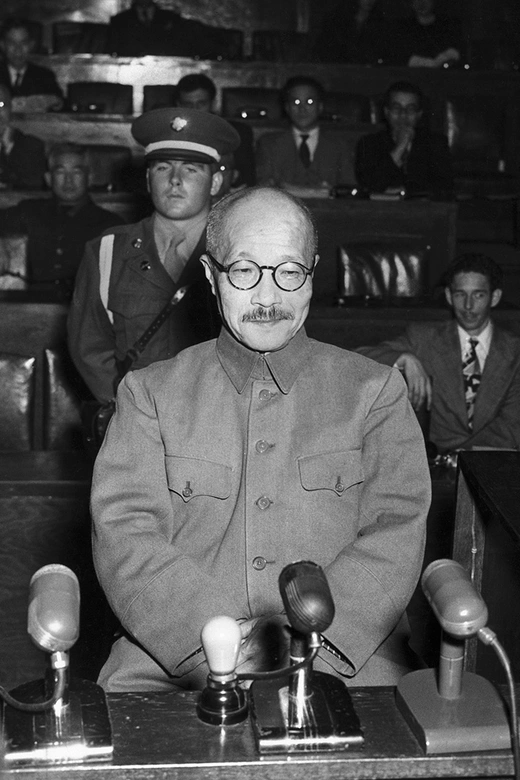

Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal Opens

The Allied powers begin deliberations on Japanese war crimes before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, a body patterned after Germany’s Nuremberg Trials. The tribunal, which ends in November 1948, presides over the prosecution [PDF] of twenty-eight government officials and military officers facing charges of crimes against peace, conventional war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Emperor Hirohito is not tried. Supporting tribunals are held to prosecute other classes of war crimes across Asia.

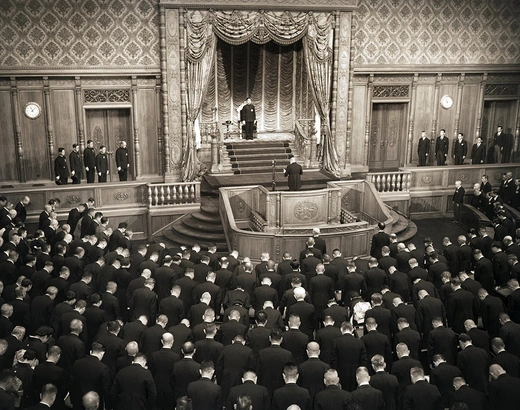

Japanese Constitution Goes Into Effect

The new Japanese constitution, promulgated by Emperor Hirohito before the Japanese parliament in November 1946, replaces the 1889 Meiji Constitution. The new constitution, with some amendments by the Japanese government, is largely the work of MacArthur and his staff, who draft the charter to protect the civil liberties of the Japanese people and establish democratic governing bodies. Article 9 of the constitution denounces the country’s right to make war and prevents the buildup of armed forces.

Korean War Begins

Following Japan’s surrender in 1945, Korea, which was a Japanese colony for thirty-five years, is split along the thirty-eighth parallel by the United States and the Soviet Union to facilitate postwar transition on the Korean Peninsula. Five years later, the Soviet-backed military of communist North Korea crosses the demarcation line and invades the South. U.S.-led UN forces enter the war to defend the South. Chinese troops also enter the war, supporting the North. In 1953, representatives of the UN Command in South Korea and military commanders from China and North Korea sign the Korean Armistice Agreement [PDF], ending the war, but they don’t sign a formal peace treaty. In 2018, North and South Korea agree to establish a peace treaty, though tensions persist and such a treaty has yet to be signed.

Japan Signs Peace Treaty

Delegates from Japan and Allied countries sign the Treaty of Peace (to take effect in April 1952) in San Francisco, returning full sovereignty to Japan and ending seven years of occupation. The United States and Japan also sign a bilateral security treaty outlining the terms under which Japan permits U.S. military personnel and bases on its soil. There are now eighty-five U.S. bases in Japan. A revised security treaty, signed in January 1960, includes a U.S. obligation to assist in Japan’s defense. Japan’s relations with U.S. ally South Korea and neighboring China remain strained over wartime actions.

Online Store

Online Store